With each network API call looking more like functions, we often didn’t notice how hard it was to create an atomic operation in a distributed environment. For instance, writing to an SQS queue in AWS can be as simple as importing the SQS Client and calling sendMessage. These network calls encapsulate into a function. Therefore, the main application will call the function and treat it as an atomic operation.

Treating a side effect like an atomic operation may cause problems to your application down the line.

A Simple Notification Service

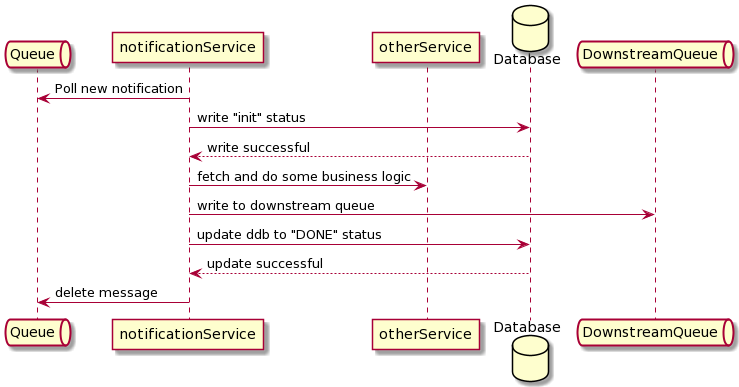

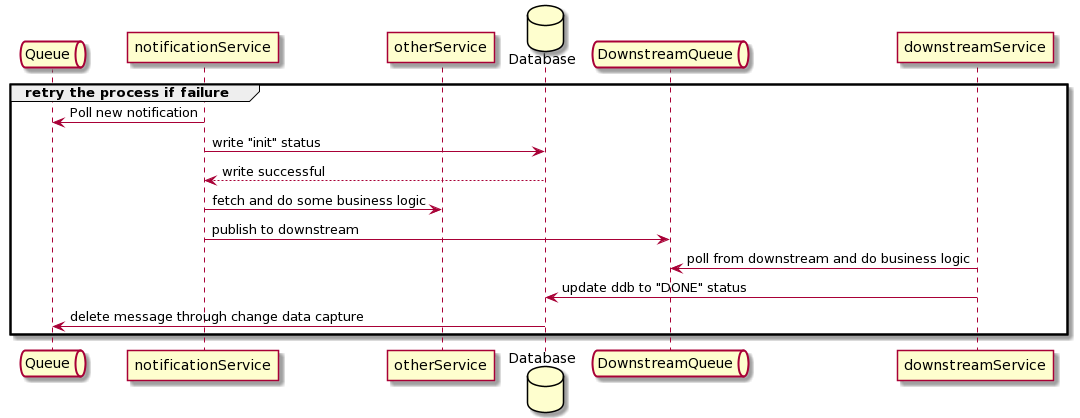

Imagine you want to create a notification service that listens to the upstream, does some business action, and sends the action further downstream.

Downstream service will write state to a database after doing various operations. For instance, you have a notification service that will receive some message from upstream about initiating a refund. The job of the notification service will first write an item to some database table with the status of INIT.

It does some aggregation and sends the message to different downstream queues. Once writing to the downstream queue is finished, the notification message will update the table and write the status to DONE. Having an internal audit database is common in microservice design as it helps with debugging, reporting, and avoid any message loss.

In this case, the notification service is designed based on at least once invariant, meaning the message will be guaranteed to be delivered downstream. For any reason, the downstream may receive more than one message.

Suppose there are any errors within the flow of the notification service. In that case, the service will re-run the flow by not deleting the queue from the upstream and retry the flow six times before putting that notification item to the dead letter queue.

Problem

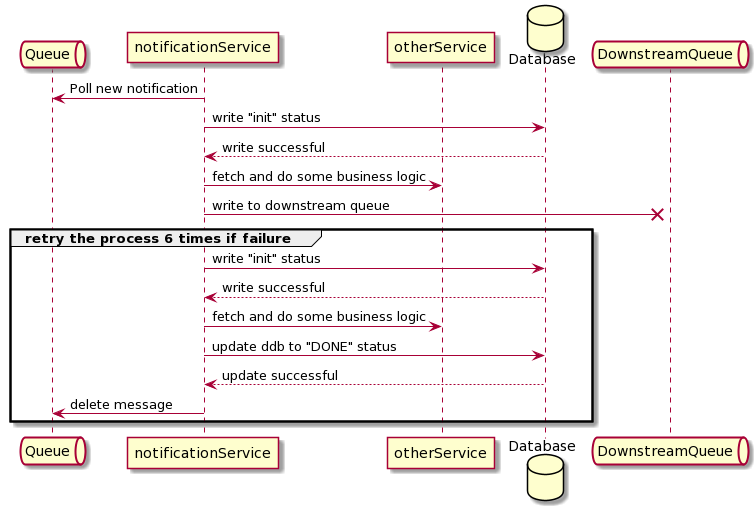

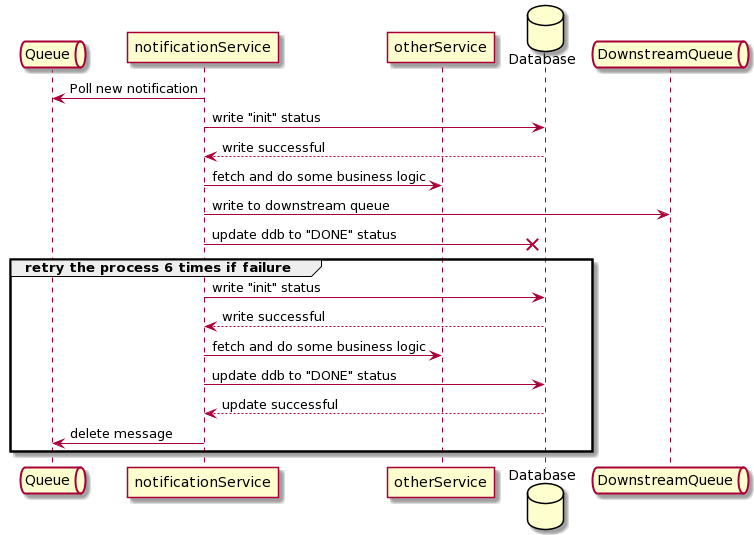

This design may encounter dual publishing. Let’s take a look at these two scenarios:

During the last stage of writing DONE message may fail.

In this case, the notification service will re-run the entire flow again. If this is a refund, there is a possibility to create a double-billing issue.

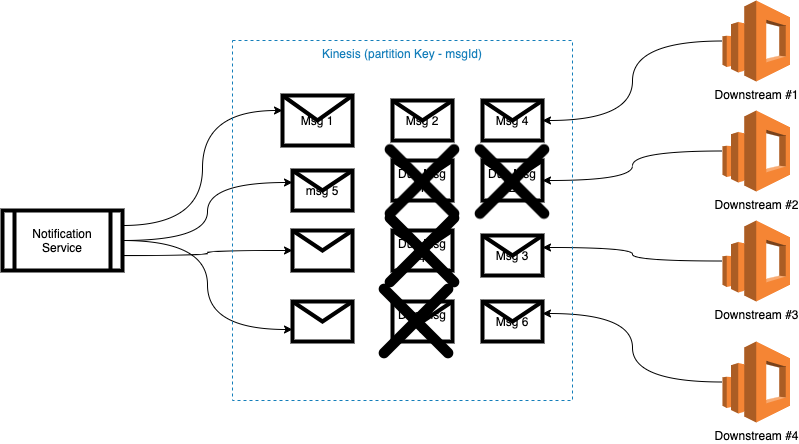

Scaling downstream causes race conditions. Because of the at-least-once delivery, there is a potential that two different instances of the downstream process the same message.

In the above example, downstream will asynchronously poll messages from the queue. Since the message broker characteristics of at-least-once invariant, Downstream#2 may get Dup Msg 1, and both downstream may run the same value.

One of the problems with the design is multiple side effects. Writing to downstream queue and update the database are two side effects.

Adopting distributed transactions can solve multiple side effects such as two-phase commits. However, two-phase commits are expensive and hard to implement.

Another problem is the infrastructure resources need to support distributed transactions. For instance, most relational databases, such as MySQL, queues like ActiveMQ, and cache, such as Hazelcast, support transactional operation.

However, they don’t support transactions if you are using AWS, such as SQS or DynamoDB. Thus, using them may cause some atomic issues if not designed carefully.

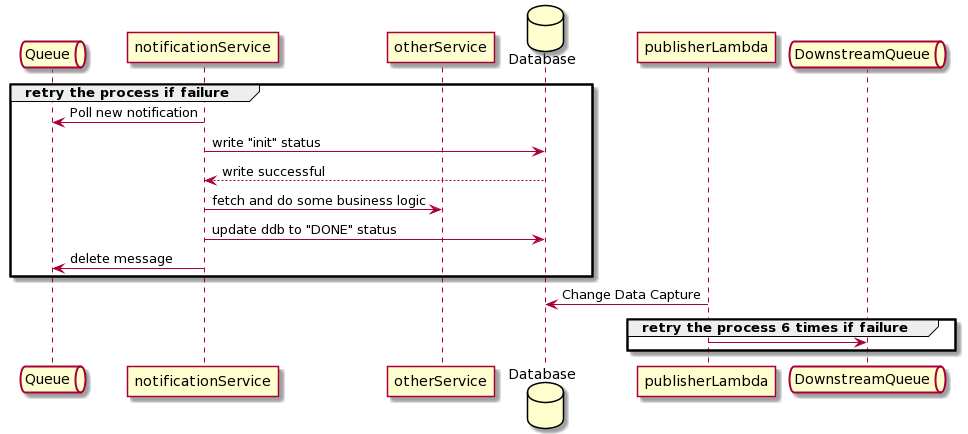

Seek for Single Side Effect

Besides having a two-phase commit approach, minimizing side effects can help decrease complexity in the system.

In the case study above, publishing a message to a queue and updating the database entry consists of two side effects. If the two operations are not transactional, the flow is not atomic.

Seek for single side effects when possible. We can use a stream-based approach and create a change data capture on the database. Instead of writing to a downstream queue and follow up with an update in the database, write to the database and use change data capture (CDC) to initiate a send request to the downstream queue. In AWS, you can use DynamoDB streams and connect the stream to an SQS or Kinesis Queue.

If any operation within notificationService failed in the above example, it can keep retrying the process and worry about downstream publishing.

Another variation of the solution is to make the downstream update the database instead of the notification service. Therefore, once the downstream accepted the transaction, it will update the database table to DONE. Using the DynamoDB table, you can set the conditional expression on the DynamoDB table write to ensure that the notification message can only write once.

Partition Problem

To address the second problem, scaling downstream causes multiple processes. We can ensure that the same transaction should go to the same partition by partition the transaction based on its identifier. In terms of AWS, using Kinesis instead of SQS and set the partition key in Kinesis to notification id.

In this scenario, in downstream instances, one cannot receive notification number 2 because notification id number 2 always goes to shard number 2 instead of shard number 1.

Closing

Atomicity is important in business applications from the case study above, but it is hard to achieve in a distributed environment.

Various cloud services, such as AWS, have provided ways to provide many resources out of the box. However, many of their resources don’t support transaction and idempotency(in some cases) out of the box.

Engineers will need to design their application in a way that decreases the multiple side effect and idempotency.

A general rule of thumb from this case study is to avoid as many side effects as possible when dealing with operations in a distributed environment and use events to create actions for other external services.