Before I explain the definition of cut vertex and cut edges, let’s try to look into this problem statement.

Given a network (graph), find the critical point (or edges) in the network, such that if we remove that point or edges, it split the network into two.

A critical point in a network is that the vertex will disconnect the web when you remove the vertex.

We can visualize a network as a graph, where each node can be an entity, and the edges represent if two entities are connected.

This point that split the graph into two is called the cut vertex.

Same with cut edges, it is a critical edge (or bridge), is the necessary edge, when remove will make a graph into two.

Let’s assumed vertices in this case since edges will be similar vertices, and we will briefly talk about finding the bridge.

So how do we solve this problem?

Since we want to find all the vertices, we will split the graph into two. We will try to remove each vertex in the graph one by one. If the graph disconnects after removing the vertex, we can add that vertex to our cut vertex bucket list.

The brute force method works. However, if we have a large graph, it will take forever to do the operation.

For every vertex, we do the following:

- Remove the vertex

- Check if the graph remains connected (we can use DFS or BFS, or Union Find)

- Add the vertex back to the graph

Imagine checking if a graph is a connected component for every single vertex. Depending on how you implement the checking connected component algorithm, you will run V*(V+E). Looping through each vertices cost V, and checking connected component on each vertices cost V+E.

As we look at the solution above closely, we realized that checking if the graph remains connected can be done by checking if there is a cycle somewhere down the neighbor connected to that vertex’s ancestors.

In graph theory, a cycle form within a vertex means a back edge. Think of it as another edge within its child node that is pointing back to the parent.

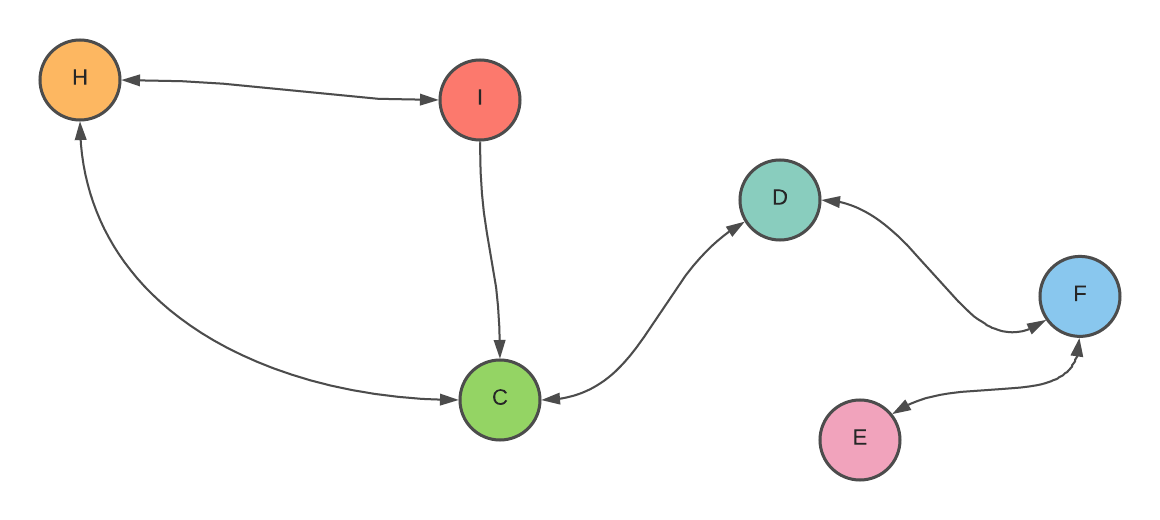

Let’s take this as an example:

[example (cut vertices)]

[example (cut vertices)]

What other condition on this vertex can determine that this vertex is the critical vertex?

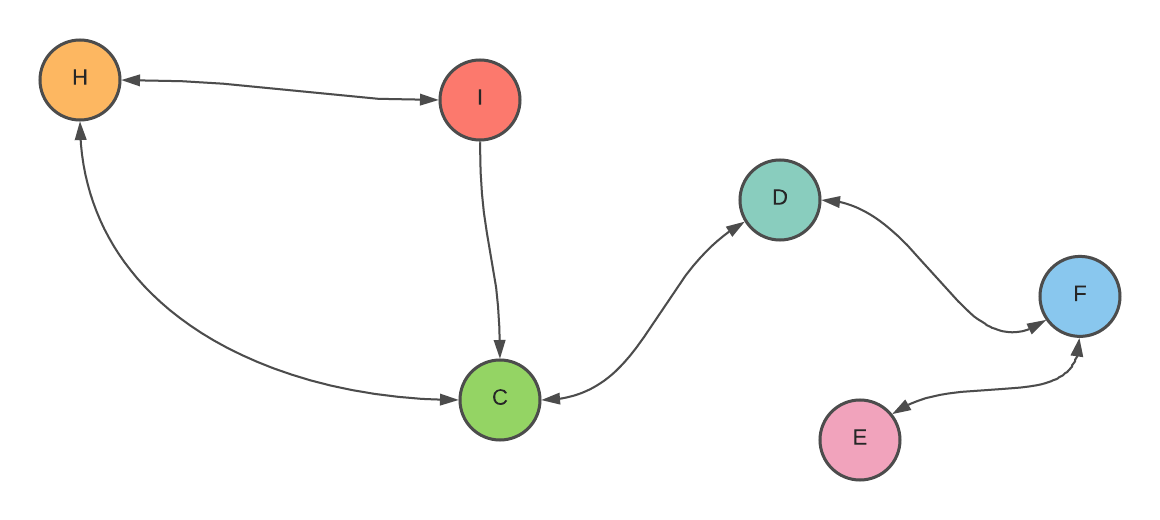

If a critical vertex’s neighbor doesn’t have a back edge pointing to its parent, we can try combining the nodes with a back edge into more significant nodes. Like this:

What did you realize?

As through observation, the elaborate graph that we saw earlier becomes a tree.

We can also conclude one thing - a graph is also a tree if it doesn’t have a cycle, acyclic graph.

Vertex C is a critical vertex because it is the root of the tree, and it has more than two children. Why two? Because if we have one child in that root and remove that vertex, the graph is still connected. If we have two children in that root and remove the vertex, it will split the graph into two.

Another point from the graph is that a leaf cannot be an articulation point because if we remove the leaf, the graph is still connected.

.png)

From all the above observation, we can see that a vertex is a critical vertex under this two condition:

- The vertex is the root of the DFS tree, and it has at least two children

- If the vertex is not the root of the DFS tree, there is no back edge from its children connected to its ancestor or to itself.

Okay, we know how the two main property that can find the articulation point. How do we determine if the parent has at least two children? How do we see if there is no back edge coming from the children’s of the vertices?

I’m glad you ask.

How do we determine if the parent has at least two children?

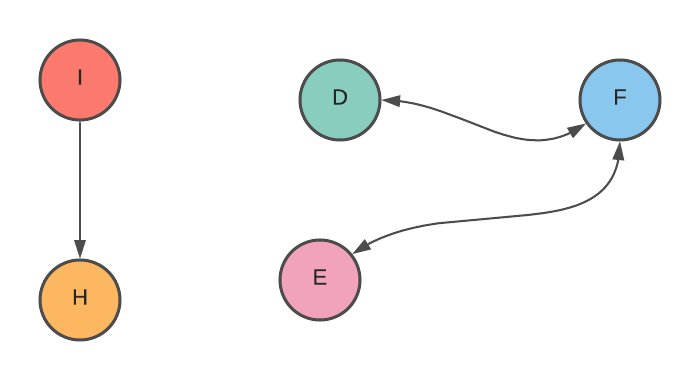

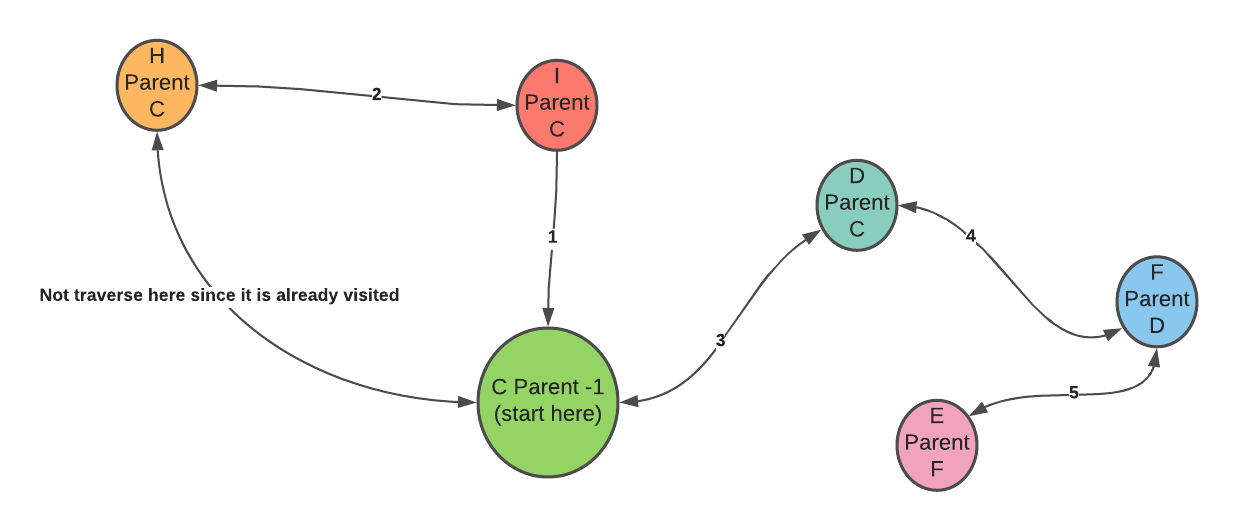

We can keep track of all the parents that we traverse at the DFS tree. Let’s say we start from vertex C. We can have a parent array where the index represents the vertices, and the index symbolizes the parent’s pointer. We set vertex C to -1. We explore its neighbor (children) and mark all the neighbor element in the parent array to C.

How do we find if there is no back edge coming from the children of the vertices?

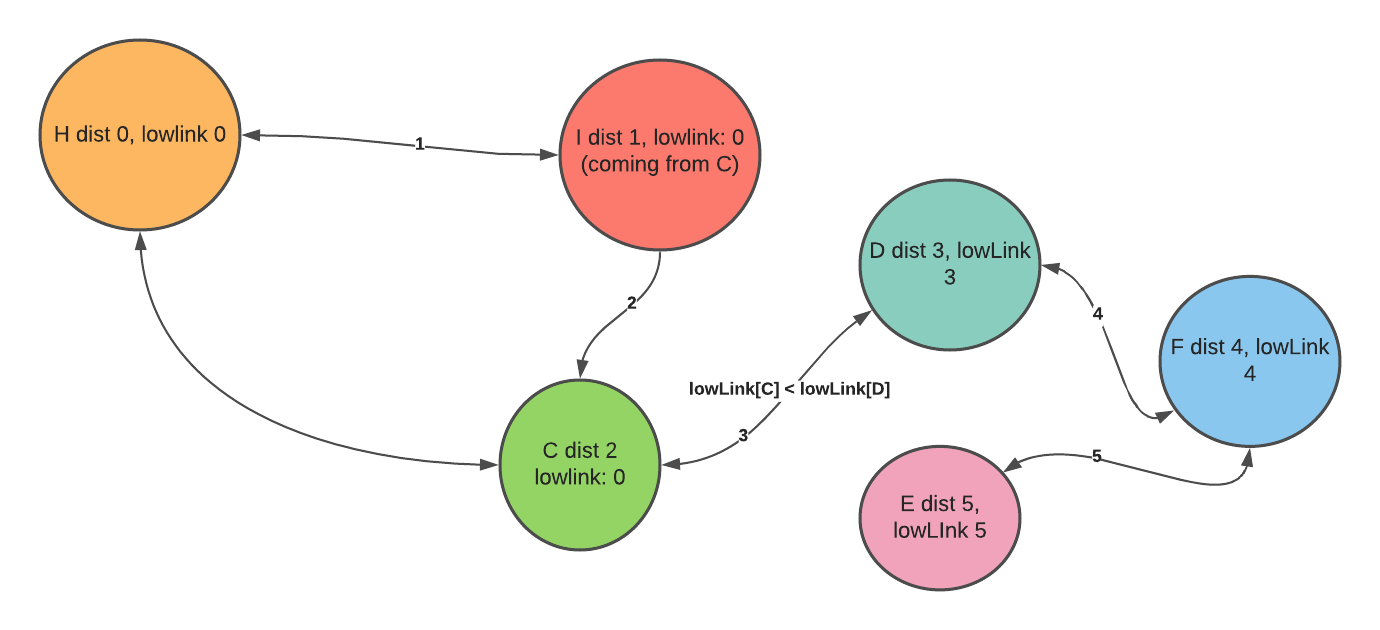

As we use DFS to traverse the graph, we can use a timestamp array to keep track of each node’s order that we traverse the graph. If we start traverse vertex C, the timestamp array element of vertex C will be 1. Then, we traverse C’s neighbor, let’s say vertex D. The timestamp array in vertex D is 1. We traverse vertex D’s neighbor, and that neighbor will be assigned to timestamp two and so on.

Why do we need a timestamp for determining the cycle?

The typical way of determining a cycle is to keep a list of all the traversed nodes during DFS operation. If a node has a neighbor pointing to the already existing list, that means the graph has a cycle.

Keeping timestamp table through all nodes helps us keep track of the first visited node in the traversal.

In the timestamp table, we can see that the operation discovers vertex D later than vertex C. With this knowledge, we can see a more specific attribute if vertex D’s can reach an earlier node timestamp table than vertex C.

To check whether vertex D can reach an earlier node timestamp table than vertex C, we need to find another array to track the lowest timestamp that can be visited from vertex D. Let’s call this ‘low ink`.

If the low link of vertex D is 0, the earliest discovery time we can reach from vertex D is 0.

What does the low link help us in finding the cycle? With the timestamp table, we can check the discovery time of each node.

With the low link, we can check the earliest discovery time that the current node reaches.

In the picture above, the discovery time of vertex A is 1. The discovery time for vertex B is 2. However, there is a back edge in the cycle somewhere in the graph that points to vertex A. We can check the low link of one of vertex B’s neighbors through the low link and see less than vertex B. If it is less than vertex B, that means the one of vertex B’s neighbor has a connection with B’s ancestor.

To find the critical point, we don’t want to have a back edge. Therefore, we can guarantee there is no back edge if any of its neighbor’s low link is greater than the current timestamp distance.

We can loop through all the vertices and do a DFS. We will have an array of visits, parents, low ink, and discovery time. For each vertex:

- Set the discovery time with the current timestamp (initial is 0 at the beginning of each DFS). Set the low link to the discovery time.

- Set the parent that discovers the vertices.

- For each recursion, we continuously change the low link by comparing the minimum of the neighbor’s discovery time and the current discovery Time.

- Once we finish setting all the low link, discovery time, and parent of the graph, we can mention the two attributes. First, we check if the current node is the parent and has more than two children. Second, we check if any neighboring nodes have a low link bigger than the current discovery time. (discoveryTime[currenNode] > lowLink[neighbor])

- If any of the two statements is true, that node is the articulation point.

Doing the above algorithm can decrease the time complexity from V*(V+E) to V+E.

Finding bridge or cut edges is similar to finding cut vertices, except it doesn’t need to check the first statement - vertices is a parent and has at least two children. Any edges that cannot cause a cycle in the graph are a bridge.

Use Cases

Cut vertices and cut edges are useful in detecting the vulnerabilities in a network because if it holds the property of a cut vertices, the network is disconnected.

We identify a single point of failure in a network, circulation, demands, fluids in pipes, and electrical circuits.

I hope you find this explanation useful! You can try to implement the algorithm as an exercise to further engrained the knowledge in your brain. This article aims to understand the algorithm’s intuition and the definition of cut vertices and cut edges. Please feel free to comment down below so others can also learn from your questions or comments.

Resource

There are some great resources about articulation points and bridges, as well as their use cases. If you are curious to learn more, check out the resources below!