Here it goes with the famous Muddy City Problem. Once upon a time, there was a city that has no roads. Getting around the city was particularly difficult after rainstorms because the ground becomes very muddy cars, got stuck in the mud and people got their boots dirty. The mayor wants to revamp the city, but he didn’t want to spend more money than necessary because it also wanted to build other things. Mayer, therefore, specified two conditions:

- Enough streets must be paved so that everyone can travel from their house to anyone else home only along paved roads, and

- The paving should cost as little as possible.

The picture above is the layout of the city. How can we determine the pave route to the cost of paving the road as little as possible?

Voíla! It is the classic question for a minimum spanning tree. Each destination can be a vertex, and the road can represent by edges. We want to create a collection of edges in the graph where the edge can reach all vertices, and the cost for building these edges is as minimal as possible.

What is a Spanning Tree? Given a graph, G, the spanning tree is a subgraph within graph G. That subgraph is a tree and connects all the vertices. A graph can have multiple spanning trees.

Since it is a tree, it will be acyclic.

The spanning tree’s cost is the total amount of weight on each edge of the spanning tree. Therefore, the minimum spanning tree is the spanning tree that where the price is the minimum among all the spanning trees in the graph. There can also be many minima spanning trees in a graph.

The two famous algorithm for finding minimum spanning tree is Kruskal and Prims. These algorithms are greedy algorithms that compute the minimum cost of the spanning tree in the graph. I want to explain both algorithm and the difference between the two.

Kruskal’s Algorithm

Kruskal’s algorithm computes a spanning tree’s minimum cost by adding the edges into the growing spanning tree. The underlying algorithm is to iterate and keep finding the pool’s minimum cost edge from the remaining edge list. Add the edge to the growing spanning tree.

The algorithm goes like this:

- Sort the edges based on their weight in ascending order.

- Initialized an empty set of growing spanning tree.

- Go through the sorted edges and do these two operation: 1. check if adding this edge to the growing set of spanning-tree will cost any cycle. If it formed cycle, skip this edge, and go through the next edge. If it doesn’t create a cycle, then add the edge to the list.

- Once you finish iterate through all the edges, the growing spanning tree will consist of the minimum spanning tree.

In the example above, we sort the edges based on their weight. The minimum edges are A -> B, B->C, and D->E, consisting of a weight of 1. Let’s choose A -> B. Then, we find the second edges, in this case, B -> C, and check if B -> C will form any cycle. Then, we check C->D, and see if C->D will form any cycle in the growing spanning tree. Then the second smallest edge is A->C, which is a weight of 2. However, we can’t add A -> C because it formed a cycle in the growing spanning tree. Skip A -> C. Then, the next smallest weight is C -> D. C->D doesn’t cause a cycle in the growing spanning tree. Add C->D to the growing spanning tree, and we finish the algorithm.

You can use either loop through the edge until the growing spanning tree has V-1 edges since the spanning tree’s total amount of edges will be a V-1 edge.

Prim’s Algorithm

Prim’s algorithm computes a spanning tree’s minimum cost by adding vertices into the growing spanning tree. The underlying algorithm will be similar to Kruskal’s, except it will loop through all the vertices until all the vertices are in the ever-increasing spanning tree.

The algorithm goes like this:

- Maintain two disjoint sets. One is the growing spanning tree, and the other is not the growing spanning tree.

- Select minimum weighted vertex adjacent to the growing spanning tree set, which is not in the growing spanning tree, and add it into the ever-increasing spanning-tree set. Choosing the smallest weight of vertices from the not growing spanning tree can do by using PriorityQueue. We can add all the neighbors of the vertex in the growing spanning tree to the Priority Queue. The priority queue will sort the vertices based on their minimum weight value. We pop the minimum weight value from the queue. Check if it is in the growing spanning tree. If it is not, we can add value to the growing spanning tree. However, we also need to account for one more thing, which will be in step 3.

- Check for cycles. To do that, we can have a boolean array that keeps track of all the vertices that are added to the growing spanning tree. Once the node is selected, we mark that vertex in the boolean array to true. Therefore, during the exploration of its neighbor, we only add the node to the Priority Queue iff the value is not yet selected.

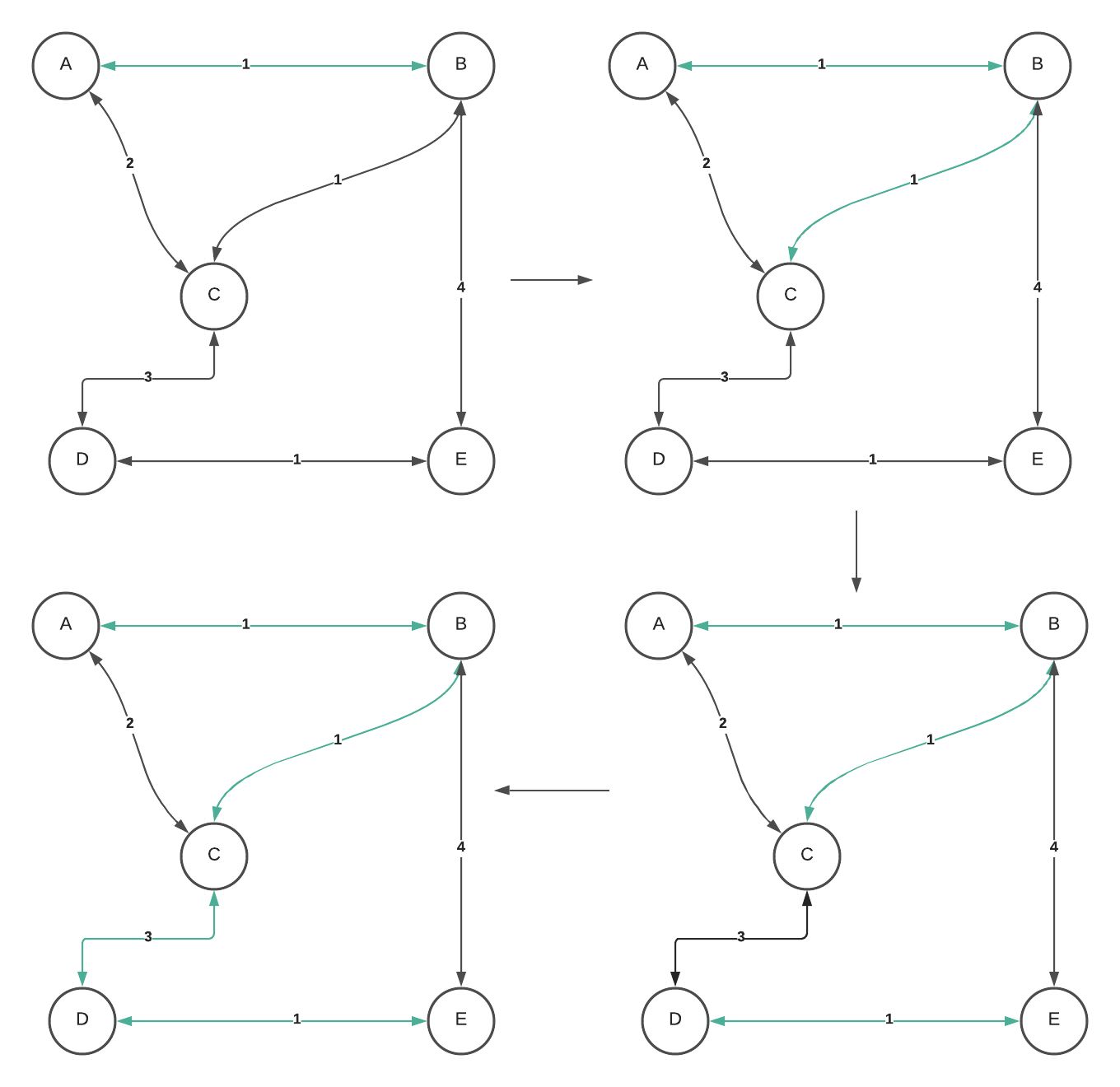

Let’s take a look at how we can see this algorithm can create the minimum Spanning tree.

The starting vertex doesn’t matter. Let’s choose the starting vertex as B. We explore neighbor B and add all the values in the Priority Queue. It consist of (C,1), (A,1), and (E,4). Pop from the min-heap, which is (A,1). Mark the vertex, explore its neighbor, and add those neighbors that haven’t been marked yet to the min-heap. On the next iteration, the smallest weight in the priority queue is (C,1). Mark vertex C and explore its neighbor. Add the neighbor to the Priority Queue. Now, we have edges with weight 3,2,4. Min heap will pop two since its weight is the smallest among others. However, we don’t add it to the growing spanning tree because the vertices will cause a cycle. Skip the operation, and pop the next smallest weight from the min-heap. So we select (D,3). Explore adjacent vertex D, and add its neighbor to the min-heap. The min-heap now has edges with weight 1,4. Prim’s algorithm will select (1,E). Lastly, it will pop the remaining value in the min-heap and finish the algorithm.

The Difference

The algorithm difference is that Kruskal’s Algorithm uses an edge to find the minimum spanning tree, and Prim’s Algorithm uses vertices.

It is about the same in terms of time complexity, depending on how you want to implement the algoirthm. However, if you use the Fibonacci heap, prims will run better than Kruskal.

For Kruskal’s algorithm, the time it takes to find the minimum spanning tree will be the ElogE. First, we need to sort the edges based on their weight, which will cost ElogE. Then, we will iterate through all the edges, and from each edge, we check if adding this edge will cause a cycle. If you use union-find to detect cycle with the union by rank and path compression, each find operation can take LG*N, which is amortized to constant. If you are doing the only union by rank, each find method will cost the disjoint set tree’s height, logV. Therefore, the second operation of iterating through all edges and check if adding an edge will form a cycle in the growing spanning-tree cost Elg*V - which is equivalent to E. Since we are finding an upper bound of the total operation, it will be ElogE + E, which will be ElogE. Since logE = logV^2, we can conclude ElogV.

For Prim’s algorithm, the time it takes to find the minimum spanning tree will be (V + E)logV. Since we construct the growing spanning tree based on vertices instead of the edge, we will need to go through all the vertices and edges. We will push all edges to the heap and remove all the edges from the heap. In looping through each of the vertices and edges, we also push all the adjacency vertices that are not in the growing spanning tree. Hence, the Priority Queue have duplicate vertices with different weight. In this algorithm, we will, eventually, add all the vertices associated with the edges to the priority queue. Therefore, the run time is VlogE+ElogE = (V+E)logE. However, the maximum amount of edges that a connected graph can have is V^2. If we substitute logE = logV^2, it is 2logV - which equivalent to logV. Therefore it is (V+E)logV. In a connected graph, V can be equal to E because max E is V^2. We can conclude that it is ElogV.

We can further optimize by using a Fibonacci heap instead of a binary heap. We will still be going through all the vertices and edges in the graph. However, because In the Fibonacci heap, the insertion will take constant time, and removal takes logarithmic time. Therefore, the total operation can become E+VlogV.

When to use one algorithm over another?

It depends on the use case.

If the graph is dense, then Prims will have a better performance than Kruskal. If the graph is sparse, Kruskal will be a better choice since it is easier to implement than Prim’s.

Conclusion

Minimum Spanning Tree is the minimum cost of edges that can reach all the vertices in the graph. There are various algorithms to solve the minimum spanning tree, and the two most popular ones are Kruskal’s algorithm and Prim’s algorithm. Both of these algorithms use a greedy approach to find the minimum spanning trees. However, the techniques are different. Kruskal’s uses an edge to put each of the edges to the growing spanning trees, while Prim’s uses vertices to add each of the vertices with the minimum weight to the growing spanning trees.

Resource

There are some great resources on the Minimum Spanning Tree, as well as its use cases. If you are curious to learn more, check out the resources below!