When developing an application, it is often useful to have some state in the application to detect the current point at which the program is executed. Often, we want to operate in sequential data streams, such as the parser, firewalls, communication protocol, or a stream of data. In some of these operations, the previously computed data is stored in some variable (State) and will often influence the program’s current execution decisions.

We can call these operations a stateful operation, where the program’s previous execution is carried over to the current implementation. Describing the program in terms of program state and statement in which the State will change is often used to have their programming paradigm called the Imperative programming.

Often, we can use variables to store our previous computed value to be used for current computation. However, you can also functionally write imperative style programming with State monad. If you don’t know what that is, check out my previous article on How to create a random number generator function without Side Effects.

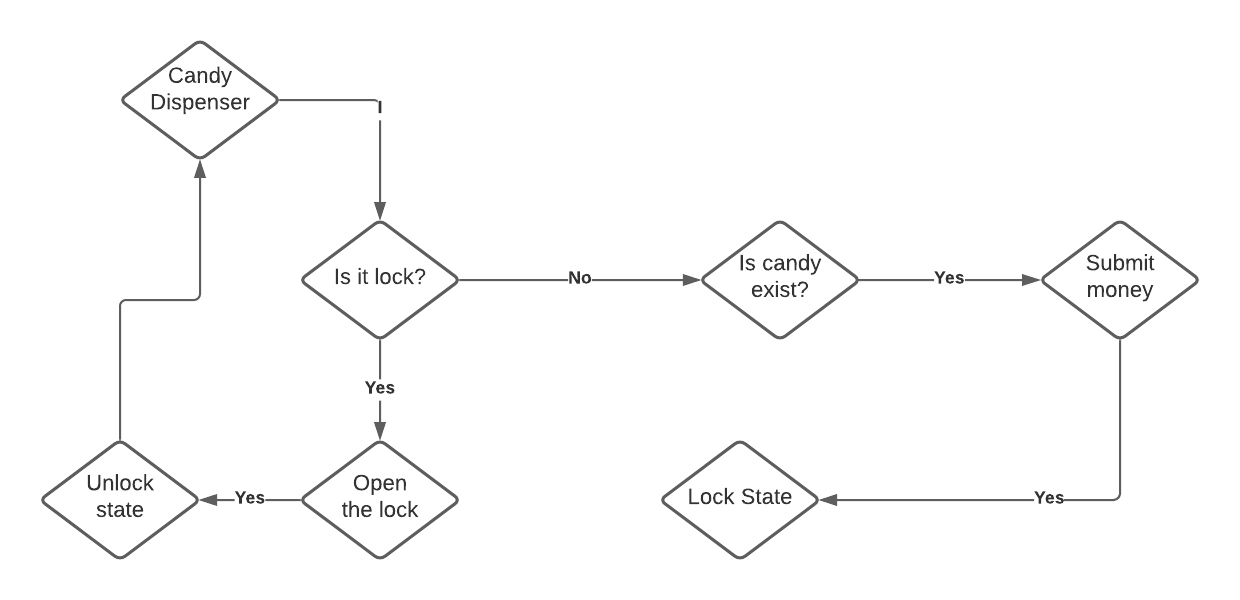

State monad is simply a function that helps you construct a finite state machine by first describing what your program should behave. You can then insert your initial State and expect to get back the final result and the final State when the program executes.

A simple value is : S => (A,S) where the function takes in S, your initial state, and return a result after computing that initial state with a value A and the new state S. For instance, if you want to create a program that will zip an array with its corresponding index zipWithIndex. A regular way of creating this function will require a for loop that will loop through an element in the sequence and zip it with the index - like this:

You can also use State to pass the state along the function.

We first instantiate an empty list of tuple (A, Int) and 0 as the first index withing foldLeft. Then on each iteration, we call the op function, creating a tuple and the next index element. The computed value will return the current result and the next State. We prepend the tuple into the accumulated List of a tuple and pass the nextI along with our foldLeft function. We only need to get the first tuple, and we also need to reverse the List because we prepend our tuple into the accumulated List.

If we have a State monad, we can also implement this with a State monad.

We first traverse the List[State[Int, (A, Int)]] to State[Int, List[(A,Int)]]. We set the State monad to have the State as the index, and the result, A, will be (A, Int). First, get the State, State.get[Int], and then set the State to index + 1. The yield statement from for-comprehension returns the result for each State. Lastly, we instantiate the initial state value, an index of 0, to execute the program.

In this article, I want to dive deep into the thought process when we want to use State monad and show you how to construct a program based on state monads.

When I first try to implement state monad’s concept to construct a program that requires some State, I don’t know how to tackle the solution. However, in this article, I’ll show you the pattern that observes while solving these problems.

Running Robots

One example is that you need to create a game where a robot is standing at one point. There will be a list of Instructions and a destination. You will need to program the robot to validate if the robot has reached the goal based on the List of Instructions that the user is giving.

Let’s define the function:

The tuple of Int represents coordinates. Each Instruction will increase or decrease the x or y coordinates from the starting point. By the end of the Instruction, we can check if the robot reaches the end destination.

Let’s try using State monad to solve this problem. We will need to create an operation of action that the robot can execute to determine the robot’s current State.

The State will be the startPoint.

The result will also be a tuple of Int.

type RobotState = State[(Int,Int), (Int,Int)]

By the time the Instruction finishes executing, we can see the history of where the robot has been in the coordinates.

Let’s create the operation in which the state should behave:

The function takes in an Instruction and the robot’s current coordinate and returns the robot’s next coordinate.

Next, let’s execute the function within the State.

We get the current coordinates. Then, we execute the action for the Instruction. Lastly, we set the new coordinates on the State, and yield the current coordinate. In this scenario, the S in State[S,A] becomes the final result, and the A becomes the history or trace that we get while executing our program.

Post Order Calculator

This refers to the Cats exercise book, where we need to implement a post-order calculator.

1 2 + 3 * // see 1, push onto stack

2 + 3 * // see 2, push onto stack

+ 3 * // see +, pop 1 and 2 off of stack,

// push (1 + 2) = 3 in their place

3 3 * // see 3, push onto stack

3 * // see 3, push onto stack

* // see *, pop 3 and 3 off of stack,

// push (3 * 3) = 9 in their place

We can implement a stack using a list. We can have the S in our State monad to be the stack.

The algorithm of the like this:

- Check if the current token is a number; if it is a number, push it to the stack

- If it is not a number, then pop two values from the stack, apply the operand with the operator, and push it back to the pile.

Therefore, let’s break down the entire flow with the transformation function. We know that we will loop through all the tokens and do some transformation. By the end of the process, we will get to the top of the stack.

Let’s implement the transformational function:

Then we given a list of token, we want to parse them:

In this case, since we don’t use the A in State monad. We can use modify to modify all the States and later get the stack’s head.

Let’s look at a more complex problem, assigning players using a finite-state automaton that models simple player assignments.

Player Assignments

One of the best examples of this is to create a finite state machine, where you give different Instructions to the program and get back the final result of the program.

Imagine you need to design a game in which n players are assigned n points from a collection of n points based on some criteria.

You want to iterate through points and alternate assignments score to n players. Therefore given a list of the score and the number of players, you will return Map of the player and the score assigned to those players.

How do we tackle this problem?

I’ll walk you through the process of how I will solve this problem.

We can first create a State monad with a State of Map[Int, Vector[Int]]. Then, we need to think of our operation on each traversal of the List of scores.

How to know which player the score is assigned to as we traverse through the List of scores?

We know that if we want to assign the score alternatively through each player, we can mod on the current index with the total number of players to score A to the player A. Therefore, while traversing the List, we also need to know what index we are currently traversing.

Let’s create an op function, which takes in the index of that sequence, the score, the previous Map value, and the player’s total number and return the new Map value to which the player will assign the value to.

Then, we need to define our State monad. We know that the State will be a Map[Int, Vector[Int]]. What will the result be?

The result can be the current index. Therefore, we can create a State monad that returns a new Map assigned value and the next iterated index value.

Now that we have already created our operation and our State’s definition, we can finally implement assignedN. Let’s implement assignedN.

This is where we realized that we need to put our index as a State to retrieve it. Let’s create a StatePlayer case class that contains the Map and the currIndex. Then, later we retrieve the Map but not the next player.

Then, we can try refactor op function to call the received a Player instead:

Afterward, we can try implementing the assignedN by using the new State definition:

You might see the pattern now, that we use traverse again on the lstOfScore. However, we want to use State.modify to only modify the State, which will return a State[Player, Unit]. The reason we want to use traverse on the lstOfScore is that traverse enabled to turn List[State[Player,Unit]] to State[Player, List[Unit]] and apply all the State within the List. We then get the last modified State of Player.

After we construct our program, we supply our program with the empty state - Players(Map.empty[Int,Vector[Int]], 0).

Most of the finite state automaton type of program that implements an imperative program is executed in this pattern. In this case, we don’t need the result of the given State monad. Thus, we use modify, because modify is get and set combine without returning any products.

In fact, I later noticed that this operation is often used that it can be abstracted and it is often called mapAccum:

Conclusion

Implementing State monad with imperative programming can be tricky sometimes. However, by creating a couple of programs, we can find a pattern that can make imperative code in a purely functional way.

We are usually using the current State, compute the next State, set it, and yield some value.

I hope you find this post useful in starting creating imperative programs using State monad and implementing algorithms in a purely functional way.