We deal with these two ways of writing complex programs all the time. If you want to reverse a linked-list, for instance, there are two ways of doing it. If you’re going to compute the number of likes in your blog post, there are iterative way and recursive ways of doing the algorithm.

However, iterative solutions are usually faster than recursive solutions when it comes to speed.

That’s it, you can stop reading from here if you want - or you can read the long answer and see why it depends.

In a standard programming language, where the compiler doesn’t have tail-recursive optimization, Recursive calls are usually slower than iteration. For instance, in Java, recursive calls are expensive because they can’t do a tail-removal optimization.

In some functional programming language implementation, iteration can be expensive because all values are immutable, and you need to copy all the discounts and mutate the data. In a multi-threaded environment, iteration can be costly because of dealing with mutator and garbage collector at the same time. Many functional languages treat the recursive call as a JUMP instead of putting it into a stack.

The key is how those values that you write get generated in the assembly language.

If you build a computed value from scratch, iteration usually comes first as a building block, and it is used in less resource-intensive computation than recursion.

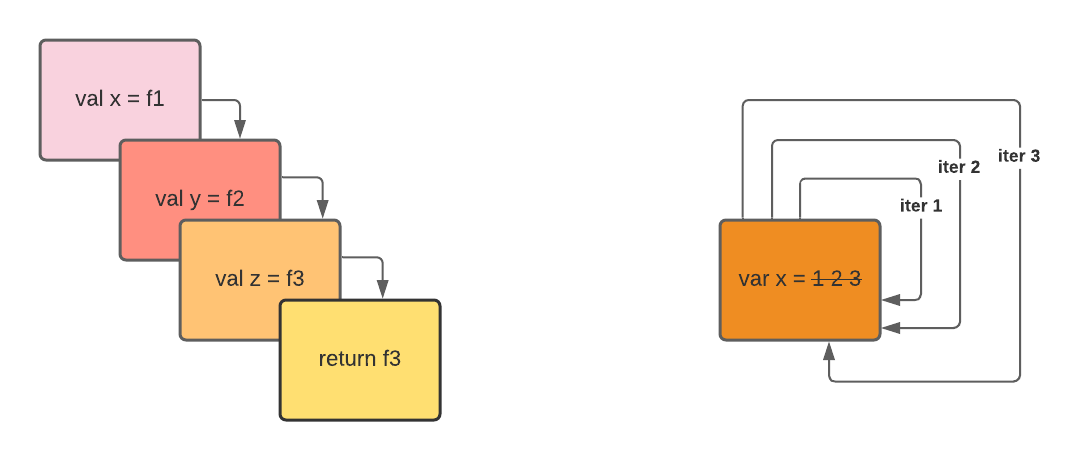

Since the initial way of writing compute values are procedural, the initial thing that we think about creating is state and memory. For instance, to do something useful on that program, we need to store some intermediate or final memory. It can be an array of memory values.

Second, a computed value will be useless if we don’t have any instructions. During my assembly language class, the ARM assembly language has MOV, ADD, and other instructions to alter the state in your compute values. Then, we add sequential instructions, such as JUMP and conditional statements, to jump to a particular execution. Multiple JUMP values in a loop are called iteration.

If we want to write more complicated compute instructions, we need to have a subroutine to jump to and execute the steps. A better implementation will be to use a stack to use multiple nested calls. You can use a subroutine to call another subroutine, which we call a function.

So, what happens when a subroutine calls itself?

Vóila, you get recursion.

As you can see, iteration comes first during the concept of design, and it is much easier to reason about in a procedural environment. In iteration, we don’t need to store an immediate result in a stack. It implies less instruction. Thus, it has fewer CPU cycles.

However, this is at the assembly line level. In the high-level code, that might be the case.

Where Recursive Call can be as Performant as Iteration

You can structure your program to be tail-recursive to make the compiler optimize and treat it as an iterative call.

Tail recursive call is when the subroutine call performs as the final action of a procedure.

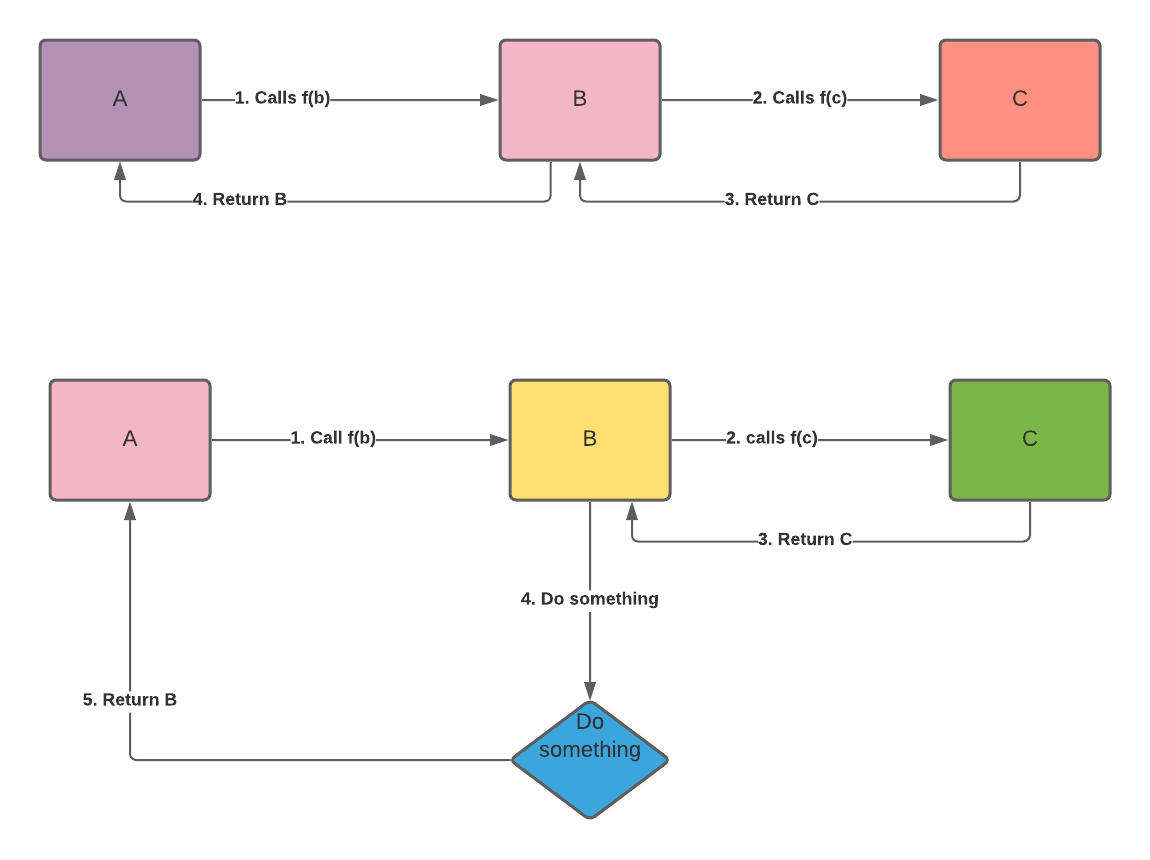

Imagine this. We have 3 functions, A, B, and C. Function A calls function B, and function B calls function C. If function A returns the value of function B, and function B returns the value of function C, the instruction can be classified as tail-recursive call. Remember, in each function call, we are storing the previous process into a stack. If we don’t do any additional operation after calling function C, keeping that value is a waste of space.

If you don’t need any variable to store function A and function B, function C doesn’t need to return to function B. You can just skip function B and function A and reuse the variable that A and B have. When the compiler knows this, they can reuse the stack frame and not keep occupying a new stack on each recursive call - making it like an iterative call.

In some language, we tell the compiler to do this. Some compiler in the language can automatically detect our code being recursive and help optimize it on our behalf. There is @tailRec annotation in Scala programming to specify the compiler to optimize the current function as a tail-recursive call. If the procedure is not tail-recursive, it will give an error in the compile time.

Once we can execute the function in a tail-recursive manner, writing a recursive solution and the iterative solution is just a matter of algorithm styles.

Closing

When it comes to recursive and iterative codebase performance, it boils down to the language and how the code owner writes the program. You can write a recursive solution that is faster than an iterative way. In terms of assembly code, iterative represent less instruction, and thus, it is much more performant than the recursive ones.

On the other hand, modern compiler leverage recursive optimization to optimized recursive computation to be the same performant as iterative solutions.

I hope you learn a little about the relationship between recursive and iterative functions and leverage tail recursion in your next coding project.

Some reference about recursion that I thought it will be helpful if you want to deep dive into this topic: